A New Artistic Agenda

Exploring a Scrutonian vision for contemporary art and our cultural institutions.

The following is a paper I delivered at the conference, “Roger Scruton: America” hosted at Georgetown University by the Center for American Culture and Ideas, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Ethics and Public Policy Center on May 19, 2024.

Admittedly, I've proposed an ambitious paper: "A New Artistic Agenda: A Scrutonian Vision for Contemporary Art." I don't claim to be a specialist in any specific form of the arts or a great public thinker like others involved in this conference. My position at the Roger Scruton Legacy Foundation has, however, led me to continually ask how we—whether we Westerners, we Americans, we conservatives, or we Scrutonians—how we can build a vision that understands art on its own terms and advances the renewal of our cultural patrimony? Many of you likely share my dismay when you look at our various cultural institutions and see the prevailing attitudes of malaise, if not outright resentment and rejection.

Examples of this ‘culture of repudiation’, as Scruton called it, are abundant. This phenomenon isn't new; we can look back to the culture wars of the 1990s, if not further, to see the trajectory leading to our current situation. Yet, the conservative response has hardly evolved. Take the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) as an example. Despite periods of respite under leaders like Dana Gioia, the Heritage Foundation's stance has remained largely unchanged since 1997, advocating for the elimination of NEA funding due to its support of what they see as wasteful and morally degrading art. While I generally agree with their critique, I question whether the solution is defunding and abolishing the NEA. This institution is charged with being a cultural caretaker of American traditions, and simply abandoning it may not be the best approach.

To understand why this approach might not be ideal, let’s take a moment to further consider the role and potential of the NEA. The National Endowment for the Arts, established in 1965, has a mission to foster the arts in America, supporting artistic excellence, creativity, and innovation for the benefit of individuals and communities. Over the decades, it has played a crucial role in promoting a wide range of artistic endeavors, from classical music and opera to contemporary visual arts and theater. While criticisms about funding allocation are valid, it’s worth considering how we might reform and improve such institutions rather than dismantling them entirely.

This brings us to a critical question: what should our vision for the arts be and what does Scruton have to do with this? For the uninitiated, I often describe Scruton as a case study in loving one's own well—including one’s community, culture, and traditions. And if we are to take Scruton and his work seriously, we must ask: what does it mean to love our traditions well, and how can we hold cultural institutions accountable as caretakers of our heritage?

In response to the culture of repudiation, we must rally around beauty, artistic excellence, and creative free expression. By looking to Scruton's work as well as the work of those he influenced and those who influenced him, we can begin to build a philosophy and vision that holds these institutions to account. This vision involves understanding and appreciating the intrinsic value of art, nurturing artists' skills and creativity, and fostering an environment where artistic expression is not only allowed but celebrated.

Understanding the Culture of Repudiation

Scruton's "culture of repudiation" describes a prevailing trend within Western intellectual and artistic circles characterized by the wholesale rejection of traditional cultural, moral, and aesthetic values. This movement, rooted in skepticism toward past achievements, seeks to deconstruct perceived oppressive legacies rather than preserving and engaging with them. Scruton argues that this repudiation leads to cultural disintegration, creating a fragmented society devoid of the continuity and meaning provided by historical traditions.

This cultural disintegration manifests in various ways. One clear example is the current state of the academy and the ongoing conflicts across our campuses. Recently, pro-Palestine protesters nearby proclaimed, "Gaza lights the spark that will set the empire ablaze." For them, the current conflict is a means to an end: the destruction of our traditions and the American identity. Such radical positions are not just isolated incidents but reflect a broader trend of rejecting the foundational values and narratives that have shaped Western civilization.

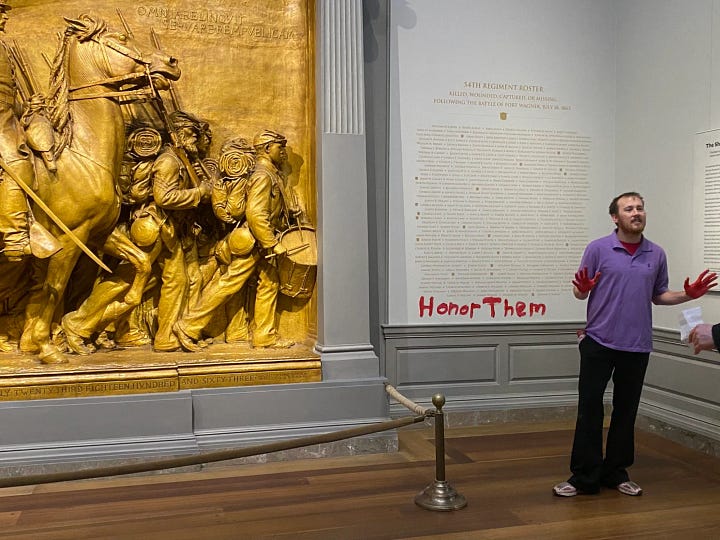

A similar phenomenon is occurring in the art world. Movements focused on "decentering whiteness" and decolonizing culture—including the decolonization of collections in museums, of the concert hall, of the orchestra, and of the literary canon—are paired with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. This attitude is widespread, as seen with the American Alliance of Museums' recently published framework promoting repatriation, restitution, and reparations as the future of American museums, or the League of American Orchestras' Catalyst Fund which provides orchestras funding to hire DEI consultants. This is coupled with the prevalence of political art and vandalism. Political art often focuses on goals related to climate change, as with the UN's Art Charter for Climate Change, or health and wellness, a recent focus of the White House. Vandalism, encompassing both physical destruction and acts of desecration, includes numerous examples such as the defacement of the National Gallery of Art memorial to the first all-black regiment in the Civil War, followed by the defacement of the US Constitution in the National Archives Museum.

These examples highlight a broader issue inherent to the culture of repudiation: the instrumentalization of art for political ends. Art is increasingly viewed as a tool to advance specific ideological agendas rather than as an expression of human creativity and a pursuit of beauty. This shift has important implications for how art is created, presented, and perceived. Instead of fostering a thriving and meaningful artistic culture, this approach often leads to a narrowing of creative expression and a devaluation of artistic excellence.

Art on Its Own Terms

So, what is the proper role of the arts? How do we understand art on its own terms?

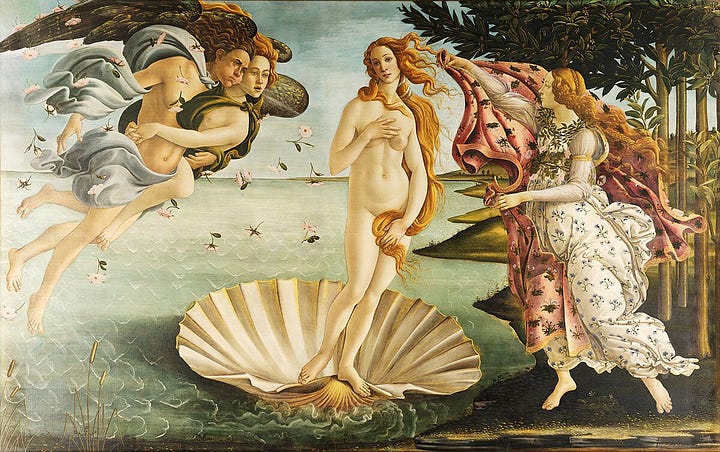

Scruton's answer is simple: art must be seen as aesthetic objects, or in the terms of German philosopher Immanuel Kant, objects inviting the "interest of reason." For Scruton, defining art was not crucial; rather, any object intended as art could be considered such. The difference between works like Andy Warhol's Brillo Boxes or Tracy Emin's My Bed and masterpieces like Botticelli's Venus lies in their capacity to invite contemplation for their own sake.

Art, properly understood, does not exist to serve political ends. While art can communicate culture, history, values, and identity and have political themes as its subject matter, its primary purpose is aesthetic. Seeking secondary benefits, such as various social advantages, misunderstands the essence of art. As Scruton put it, good art offers "a self-conscious placing of ourselves in relation to the thing considered, and a search for meaning which looks neither for information nor practical utility but for the insight which religion also promises: insight in the why and whither of our being here." (Modern Culture, p 39)

Understanding art on its own terms involves recognizing its intrinsic value. Art can elevate the human spirit, providing a sense of connection to something greater than oneself. It can also serve as a medium for exploring complex ideas and expressing profound truths about the human condition.

A New Artistic Agenda

Understanding the proper role of art, we must ask: what does it look like to create a vision for contemporary art that embodies "a new artistic agenda"?

I propose that this new artistic agenda, applicable to any art institution, should focus on three principles: (i) beauty, (ii) artistic excellence, and (iii) creative free expression.

I. Beauty

Although he wrote an entire book on the subject, Scruton refrained from giving a precise definition of "beauty." Instead, he saw beauty as something that evokes a "disinterested interest." Drawing on Kant, this concept means taking pleasure in something for its own sake, without any practical benefit. "Aesthetic interest" is a form of this then, which judges beauty in objects purely for its own sake and experiencing a contemplative pleasure that transcends mere sensory enjoyment. This requires setting aside personal desires and utilitarian considerations to fully appreciate the intrinsic value of the beautiful object. Thus we get Oscar Wilde's famous statement that "all art is useless.” Beauty, in this sense, invites us to contemplate and engage with the world in a manner that transcends immediate practical concerns, allowing us to experience a higher form of satisfaction and meaning.

Central to Scruton's understanding of beauty is the idea of "fittingness," which refers to the harmonious relationship between the parts of a work of art and its overall form. This creates a sense of coherence and order that is essential for the perception of beauty. Even works depicting pain and suffering can be beautiful if they induce a contemplative response. For example, the haunting beauty of Caravaggio's "Denial of St. Peter" lies in its use of shadow and color, drawing us into the human drama and provoking thoughtful reflection on themes of betrayal and repentance.

Beauty, according to Scruton, is a real and universal value anchored in our rational nature. It ennobles the human spirit and presents us with a justifying vision of ourselves as something higher than nature and apart from it. This view emphasizes that beauty is not only about sensory pleasure but involves a deeper engagement with the object that reveals its intrinsic worth.

For institutions, the pursuit of beauty requires creating and promoting art that successfully piques the ‘aesthetic interest’. Institutions must prioritize beauty by supporting artists dedicated to creating works that resonate deeply with the human spirit, offering insight and meaning that transcends the ordinary. By fostering an environment where beauty is valued and pursued for its own sake, institutions can contribute to a cultural landscape that ennobles and elevates the human spirit.

II. Artistic Excellence

Proceeding to artistic excellence, the simplest definition I mean in things like attention to skill and craft, excellent form and content, and proper training and execution. However, this raises questions about whose standards of excellence we uphold. There are three key aspects to consider here: tradition, skill, and valuing an artist’s ability over their background.

T.S. Eliot, in his essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent," argued that tradition gives art meaning through a "historical sense," which is crucial for creating meaningful work. This historical sense involves perceiving the past as both past and present, allowing artists to engage in a dialogue with the entire continuum of art history. Eliot emphasized that tradition is not a static inheritance but a dynamic engagement requiring great labor to understand and internalize. True artists do not merely imitate their predecessors but create works that are both contemporary and timeless, fitting within and altering the existing order of past masterpieces. Eliot highlighted that no artist has complete meaning alone; their significance is measured in relation to the works of past artists. This principle implies that the value of new art is judged by its ability to fit within and enhance the ongoing dialogue of tradition. By engaging deeply with this tradition, artists ensure it remains a living, evolving entity, thus addressing concerns about "whose standard" determines excellence.

Second, skill. This includes the technical proficiency and craftsmanship essential for creating high-quality art. Avelina Lesper, a Mexican art critic known for her defense of traditional artistic standards, has been a vocal critic of contemporary art trends that prioritize concept over skill. Lesper argues that true art requires mastery of technique and an understanding of the medium. This mastery allows artists to convey their vision with clarity and precision, ensuring that their work stands the test of time. She critiques the prevailing dogma in contemporary art, which often elevates concept and context over technical execution, resulting in works that lack aesthetic value and are sustained only by rhetorical justification. Lesper's insistence on skill underscores the importance of rigorous training and the disciplined application of artistic techniques, which she believes are indispensable for creating art that resonates deeply and endures through generations. By prioritizing skill, we ensure that the works produced are not only intellectually engaging but also visually compelling and technically sound.

Third, we must value an artist's ability over their background. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on diversity and representation in the arts. While inclusivity is important, it should not come at the expense of artistic excellence. The focus should be on the quality of the work and the skill of the artist, regardless of their background. This approach ensures that the arts remain a meritocratic field where talent and dedication are the primary criteria for success. It also allows for a rich and diverse cultural landscape where the best works can be appreciated and celebrated.

III. Creative Free Expression

Finally, we must emphasize the importance of creative free expression. This principle involves upholding the freedom of artists to explore a wide range of topics and ideas without undue restrictions. Artistic expression should not be stifled by political correctness, fear of offending sensibilities, or any ideological constraints, whether political or religious. Instead, artists should be encouraged to explore worthwhile subjects in an honest and sincere way.

George Orwell's perspective in his essay "The Prevention of Literature" is particularly useful here. Orwell argued that true creativity flourishes in an environment where artists are free to explore controversial and challenging subjects without fear of censorship. He believed that freedom of expression is essential for the creation of art that is both intellectually and emotionally engaging. Orwell's insights highlight the danger of stifling artistic expression through ideological conformity, which can lead to a sterile and uninspired cultural landscape.

However, I would add that this freedom comes with the responsibility to avoid creating trite or degrading art. The freedom to express oneself artistically should not be a license to produce art that is sentimental or kitsch. Scruton emphasized that genuine artistic expression must transcend mere emotional manipulation of sentimentality or the fake reality of fantasy. Instead, it should engage with deeper truths and provoke thoughtful reflection.

For institutions, promoting creative free expression means protecting artistic freedom while also encouraging artists to strive for excellence. Creative free expression is a necessary component of a renewed artistic culture, but it must be balanced by the principles of beauty and artistic excellence. Without these guiding values, the freedom to create can lead to art that is aimless or purely provocative without substance. We wish to create art that is not aimed at pleasing the political fads of the day, but speaking to the deeper transcendent truths of the human condition.

Concluding Thoughts

The new artistic agenda I propose is grounded in the principles of beauty, artistic excellence, and creative free expression. To implement this vision, art institutions must prioritize beauty by curating exhibitions that inspire and uplift, and by supporting artists dedicated to creating meaningful works. They must invest in artistic excellence through high-quality education, training, and celebrating artistic achievements, while fostering collaboration among artists and scholars. Promoting creative free expression involves creating space for the open exploration of art, where dialogue and debate can occur free from ideological constraints.

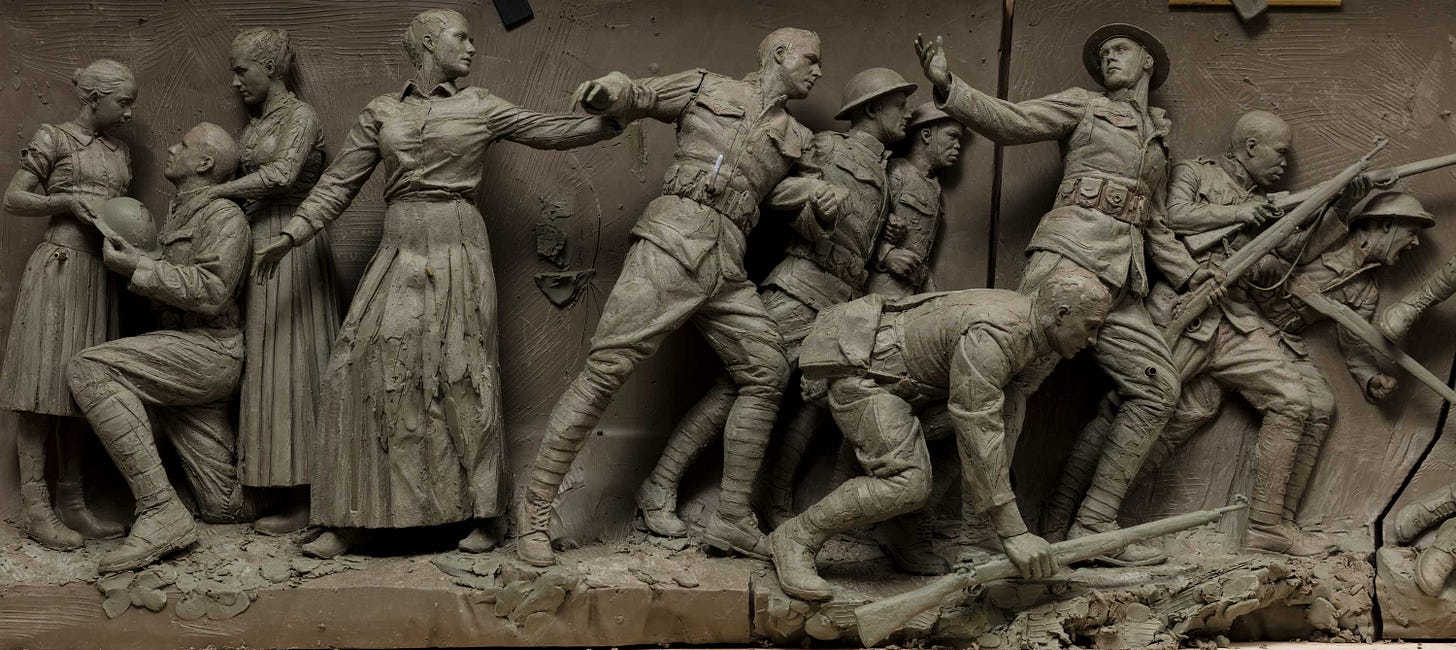

Rays of hope shine through individuals and organizations embodying these principles. Visual artists like Jacob Collins and Sabin Howard, composers like Daniel Asia and James MacMillan, poets such as Dana Gioia and Alice Gribbin, and architects from the Notre Dame School and Driehaus Prize group all exemplify a dedication to beauty and excellence. The American Contemporary Ballet, led by Lincoln Jones, stands out despite challenges due to its commitment to artistic integrity. Institutions like the Roger Scruton Legacy Foundation, the National Civic Art Society, the Center for American Culture and Ideas, and the Foundation for the Future of Classical Music tirelessly promote these values.

This agenda is not just about preserving the past but inspiring the future. Let us commit to building a cultural landscape that ennobles the human spirit, presenting us with a justifying vision of ourselves as something higher than nature and apart from it. By integrating beauty, excellence, and freedom, we can create a world where art continues to inspire, challenge, and elevate us all.

Excellent opening essay, Fisher! I look forward to reading your future posts.

Thank you for writing this. We need new cultural movements in the West.

You might want to check out the Institute of England on SubStack. It looks to reflect upon English Cultural Heritage. It is a non-political, non-nationalistic newsletter. I write articles using the Scrutonian lens I picked up from his book England, An Elegy.

It also looks to support other cultural movements, by creating a link to English culture outside the highly political Culture War.