The Power of Patronage

How Cold War politics, covert cultural diplomacy, and America’s financial elite reshaped the art world, and what it means today.

The art world presents itself as a place where taste, merit, and cultural fashion determine which movements succeed and which fail. But Abstract Expressionism—the style that came to define American modern art—did not achieve its dominance organically. Its rise was shaped by government agencies, philanthropic elites, and cultural institutions that promoted it as a symbol of American values. Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning rose to prominence as their work was positioned as a symbol of American influence.

Weaponizing Art for the Cold War

As the Cold War escalated in the late 1940s and early 1950s, culture became a battlefield. The U.S. saw the arts and humanities as a tool of ideological warfare, using them to project the image of a free, innovative, and sophisticated society in contrast to Soviet control over cultural production. By championing modernism, policymakers and institutions positioned American democracy as the incubator of artistic liberty. Abstract Expressionism, with its emphasis on individual expression and rejection of rigid forms, was ideal for this purpose.

The CIA played a major role in this effort. Through the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the agency covertly funded exhibitions, journals, and institutions from 1950-66 to promote avant-garde art and non-Soviet left-wing thought. The goal was to position America’s artistic and intellectual freedom as the antithesis to Soviet cultural control, reinforcing ideological narratives on a global scale.

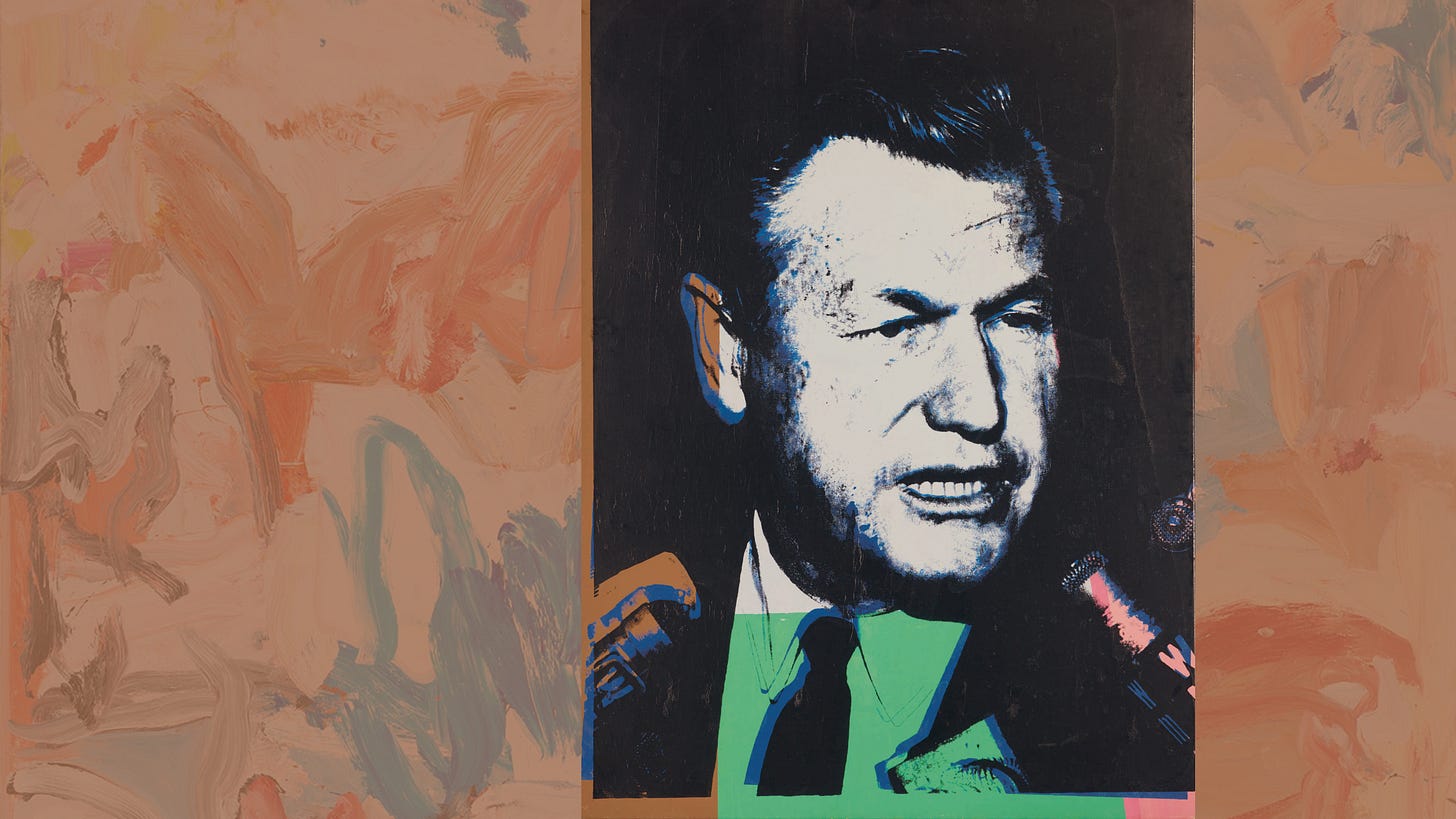

Nelson Rockefeller’s Modern Art

If the CIA provided the strategy, the Rockefeller family provided the infrastructure. Nelson Rockefeller, one of the most powerful art patrons in American history, had a deep personal and financial stake in modernism. His mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, co-founded the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1929, and Nelson himself served as president of the board multiple times. More than just a collector, he was an active force in determining what art would be displayed, collected, and celebrated.

Calling Abstract Expressionism “free enterprise painting,” Rockefeller saw it as the artistic embodiment of capitalism. Under his leadership, MoMA aggressively acquired works by Pollock, Rothko, and de Kooning. Its International Program worked directly with the State Department, the Congress for Cultural Freedom and other donors to fund exhibitions across Europe, reinforcing modernism as the aesthetic of American democracy. Yet for modernism to take hold, institutional support was not enough. It also needed a market.

Corporate backing provided the next step. In 1959, David Rockefeller, Nelson’s brother, launched Art at Work to decorate the new Chase Manhattan Bank headquarters. The program began with a generous budget of $500,000—roughly $5.5 million today—for acquisitions, with each piece appraised at $500 or less. Rather than focusing on established artists, the program prioritized lesser-known and emerging figures. The strategic move kept costs low while reinforcing modernism’s legitimacy in the corporate world. The initiative sent a clear signal: if America’s financial elite embraced modernism, so should collectors and corporations.

Meanwhile, philanthropic giants like the Ford and Carnegie Foundations—alongside the Rockefellers’ various grant-making vehicles—poured money into exhibitions, fellowships, and publications that celebrated modernism. Many of these efforts, as later Senate investigations revealed, were also quietly linked to CIA cultural strategies. Traditional government funding would have been too obvious so the agency laundered its support through philanthropic cover.

Nancy Hanks was a key player in the Rockefellers’ cultural network, helping to solidify their influence over public arts funding. Before leading the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), she shaped national arts policy at the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and founded the American Council for the Arts (now Americans for the Arts).

When she took charge of the NEA in 1969, the Rockefellers’ influence had already permeated state arts councils, following the model Nelson had pioneered in 1961 as governor of New York. The NEA fit seamlessly into the private-public patronage system the Rockefellers had spent decades constructing.

A Lesson in Cultural Power

Abstract Expressionism’s triumph came at a cost. Traditional and realist art—once central to American painting—was sidelined, dismissed as old-fashioned or provincial. Classical training in composition and technique faded from art schools. The public, long drawn to representational art, was expected to embrace modernism as the pinnacle of artistic achievement, even as much of it remained inaccessible.

But artistic movements do not develop in isolation. They are shaped by those who control funding and institutions. The Cold War’s strategic promotion of modern art was a masterclass in cultural influence, a reminder that taste is never neutral but dictated by those with the vision and resources to impose it.

The institutions that shape art today may be different, but the underlying questions remain. Patronage still determines which artists and movements receive attention, funding, and institutional support. If we care about the future of art, we must also care about the forces that shape it and ensure they serve work that is lasting and meaningful.

This is the first in a four-part series on how power, politics, and patronage shape American art. From the Cold War to the present, the forces behind arts funding have determined what styles flourish, which artists succeed, and how institutions define cultural value. The second part, Public Art Captured, examines how today’s institutions, captured by ideological agendas, stifle excellence and artistic freedom.

Sources & Further Reading

Bauerlein, Mark, and Ellen Grantham, eds. National Endowment for the Arts: A History 1965-2008. National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., 2009.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. The New Press, New York, 2000.